(RNS) — It has been 100 years since a race massacre destroyed the Greenwood community of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and we are only just beginning as a nation to confront the multiple meanings and implications of this horror of American history.

On May 31, 1921, 37 blocks of the affluent African American community were destroyed by rampaging whites. One white Tulsan labeled a photograph of the carnage, “Running the Negro Out of Tulsa.”

It was not an anomaly at the time. Black World War I veterans had been singled out, especially during post-World War I “race riots,” most famously but not exclusively in East St. Louis in 1917 and during the “Red Summer” of anti-Black violence two years later.

RELATED: 100 years later, Black church leaders seek reparations for Tulsa massacre

In Tulsa, Black veterans sought to secure due process for a young Black man who had been arrested for allegedly attacking a white woman, hoping to prevent his lynching. White racists responded with a massive act of war, including an aerial attack, on stores, houses, businesses, professional offices, a hospital, a theater and churches.

At least 150 and possibly as many as 300 people died and more than 10,000 were made homeless; of these, 6,000 were rounded up and placed into an internment camp.

I first learned about the Tulsa “riot” from a Q&A item in Parade magazine in my Sunday paper sometime between 1968 and 1970. Someone inquired if any American cities had ever been bombed from the air, and the answer was Tulsa during a 1921 “race riot.”

At the time, “race riot” meant one thing: ghetto uprisings and threats of civil disorder posed by “militant” Black people responding to “white racism.” Those ghetto rebellions were usually ignited by confrontations with the police. When I read that tiny item in Parade, I was mystified that a “race riot” could occur in a place that was neither a northern ghetto nor a southern state. This was not the South that my Georgia-born grandmother vowed to “stay from” whenever asked if she was “from the South.”

It wasn’t until 1984, when I was invited to speak at a conference on “Women and Religion in America” sponsored by the Canterbury Center for United Ministry at the University of Tulsa, that I encountered Greenwood itself, and its story. I also received a crash course in Tulsa history and its struggle to heal from the horrors of 1921.

Earlier that year, Tulsa clergy organized an ecumenical service in honor of The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., using a North Tulsa (Black) Baptist church. When a Unitarian minister — a white woman — attempted to mount the pulpit, members of the all-male deacon board blocked her access. It was a disaster.

The Rev. Robert R.A. Turner, left, draws attention to the 1921 Tulsa Massacre every week in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Courtesy photo

In an attempt at reconciliation, one of the local pastors, the Rev. Melvin Bailey, Sr., invited me to preach the Sunday morning of my visit at his Shiloh Baptist Church in North Tulsa — “from the pulpit” and not to speak “from the floor.” I was to be the first woman to preach from a Baptist pulpit in North Tulsa.

Because my preaching “from the pulpit” would be historic, I was invited to a breakfast meeting the day before with a Black ministers’ group, one member of which had come prepared with two Bibles to argue against women in ordained ministry. Arriving at a Black restaurant where I was the only woman, I saw a restaurant filled with Black ranchers all clad in boots, round-topped cowboy hats and sheepskin jackets.

Afterward, I was given a tour that showed me that Tulsa was still a rigidly segregated city — North Tulsa was the Black community and the rest was white. A bridge named for King pointed one way into North Tulsa — Black Tulsa. Black Tulsans saw that as significant.

Race mattered so much that their white congressman had moved into North Tulsa to honor the significance of the Black vote that secured his election. I also learned that the unhealed pain of the 1921 race massacre was so significant that elderly people still spoke of it in hushed, terrified tones. As we crossed the King Bridge, I learned the memories included “mass graves” and “bodies floating in the river.”

By the time I gave my paper on Sunday afternoon, coming straight from the Baptist pulpit to the university lectern, I had learned how truly horrible and unhealed Tulsa’s history was.

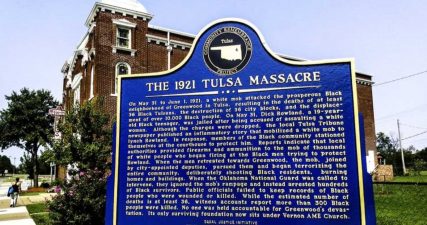

A historical marker outside Vernon AME Church about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy of Tulsa2021.org

Unspoken and unspeakable, the Greenwood Massacre is a painful bulwark in the broken soul of America. These survivors of the Tulsa Massacre were part of a larger, trauma-filled history of oppressions: Multiple trails of tears to Oklahoma made room for slavery in the deep South. In earlier generations, an estimated 1.5 million African Americans were chained and marched in coffles into the deep and western South, including Oklahoma and Mexico’s Texas. Tulsa’s Greenwood is a rock in a river of America’s internal migrations, and the massacre in turn helped to send many thousands north in the Great Migration as refugees in their own land.

Centennials can be occasions for asking and answering the question famously asked by Toni Cade Bambara in her novel “The Salt Eaters”: “Do you want to be healed?” Centennials can be reflection points and inflection points about meanings and missions.

On May 31, 2021, such a moment will confront the United States of America. We are still being asked, “Do you want to be healed?” One hundred years after Tulsa’s riots, the search for the mass graves has only just begun. Insurance claims remain unpaid. Reparations are still resisted. A 107-year-old Tulsa survivor, Mrs. Viola Fletcher, still bears witness to the vivid memories of blood and fire, of smoke and death.

On May 19, 2021, Mrs. Fletcher testified before the House Judiciary Committee along with two other survivors. And she has lived to admonish the nation to remember and officially recognize this horror. “I have lived through the massacre every day,” she told the panel. “I am 107 years old and have never seen justice. I pray that one day I will. I have been blessed with a long life — and have seen the best and worst of this country. I think about the terror inflicted upon Black people in this country every day.”

This centennial occurs as we are facing a confluence of the streams of anti-human historical horrors — Asian American and Pacific Islander hate, Islamophobia, antisemitism, xenophobia, homophobia and anti-transgender violence, and so much more deeply rooted in American dreams and nightmares. If we want to be healed, we must remember and address unresolved injustices. The voices of Greenwood survivors are asking this nation to seize an opportunity to do that.

(Cheryl Townsend Gilkes is the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of African American Studies and Sociology at Colby College and an assistant pastor for special projects at the Union Baptist Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is the author of “If It Wasn’t for the Women: Black Women’s Experience and Womanist Culture in Church and Community.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)